Generalization is the process of transferring skills taught in one set of conditions to other conditions. This includes transferring the skills into other settings, to other people, to other materials and stimuli, and to other activities. In short, the purpose of generalization is to translate skills taught in the classroom to the real world. Repeatedly, it has been shown that individuals demonstrate difficulty generalizing skills to different conditions. As a result, careful attention must be paid to systematic generalization of skills in individuals .

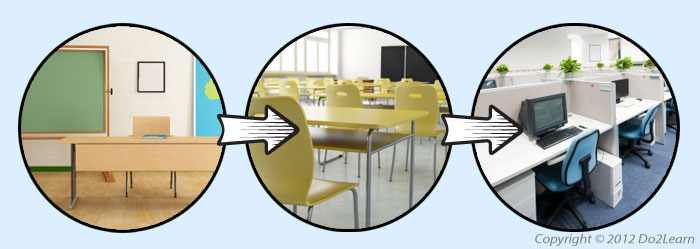

When we think of generalization, we most often think of generalizing a skill from one setting into other settings. For example, we might teach a student how to ask for help when needed in the classroom. This skill of asking for help must then be transferred, or generalized, into the work place so that the student is able to ask for help in that setting as well.

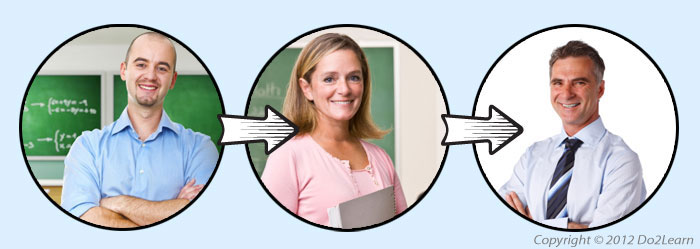

Additionally, a student may associate a certain skill with the person who taught him that skill. They will not generalize that skill to other people. Using the same example as above, a student may learn to ask for help from one teacher, but does not use the same skill when she needs help from other teachers, her supervisor at work, or her mother at home. She associates asking for help with one teacher. Thus, generalization must occur not only to other settings, but also to other people.

A student may associate a particular response with a particular item, question, statement, exemplar /representation, or object. If the behavior of asking for help is associated with the question, “What do you need?” then the student might not ask for help unless that question is first presented. In reality, this question is a prompt and will not promote generalization.

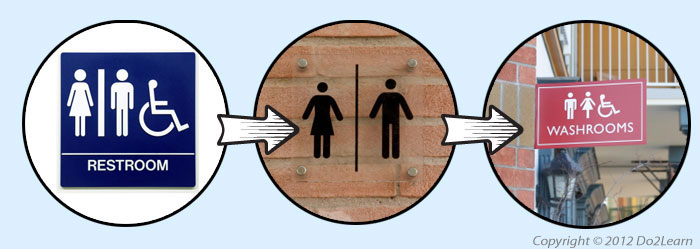

As another example, if a student will only identify one particular representation of a “restroom” icon and does not recognize other “restroom” icons that vary in color, shape, or form, then the student has not generalized the representation of “restroom.” He might not be able to locate a restroom in a vocational or community setting unless the environmental print looks exactly the same as the one he was taught to label in the classroom.

Similarly, a student may associate a certain learned skill with a particular task. If taught to ask for help when doing office tasks, she may only ask for help during those particular tasks. Thus, the student needs to be taught to ask for help when doing other tasks, such as cooking tasks, academic tasks, or domestic tasks.

Why is generalization so important?

Generalizing skills from the teaching context to real life applications is incredibly important. A skill mastered in the classroom but not applied to real life situations is not useful. For example, understanding the concept of personal space, but not actually applying it, does not do the individual any good. Despite its importance, the process of generalization is often overlooked. Generalization is often treated as an afterthought, rather than carefully considered when a new skill or response is first targeted.

Professionals working with individuals must take systematically arranged and integrated steps to ensure that generalization of skills occurs into other contexts. We should not assume that the skills they teach in the classroom automatically transfer to real life applications. In many circumstances, skills do not automatically transfer. While the student knows the rule and is able to recite the rule, he or she may not actually apply the rule.

An individual may require more practice in using a concept or skill than another student because of the difficulty thinking of and applying the concept in differing environments, with different people, with different materials, and across different tasks. Learning a skill may be interpreted by the individual as applicable only with one specific set of materials. This difficulty applying a concept in different situations may be incorrectly perceived as rigidity. Teaching and applying skills in multiple circumstances helps a person develop the generalized concept.

How to generalize skills

There are many ways to generalize skills, and the most effective way will depend on the individual and the situation.

Here are some guidelines for generalizing skills from the classroom context to the workplace.

Plan for generalization up front.

Additionally, assess your student’s current skills and level of understanding to know how to teach the next skill.

Teach the skill in a familiar setting with a familiar person.

Practice the skill with multiple people.

For example, an educator may determine that a student requires explicit instruction in initiating conversations. The educator uses a situational story to introduce the topic. She reads the story with the student at a desk and asks comprehension questions about the story. After teaching the rules and reason behind the rules through the story, the teacher models the skill, and provides repeated opportunities for the student to practice the skill in role play scenarios with her. Once the student has mastered initiating a conversation with their familiar teacher, this teacher then engages the student in additional role-play opportunities with another student in the class, and then another student, and so on. Then, the student practices initiating conversations with an assistant teacher.

It is important to note that as the student practices the skill with new people, the instructor may need to initially provide close monitoring, feedback, and perhaps prompting that is quickly and systematically faded. Generalization involves much more than just sending a student into a new context and hoping that the student will display the behavior the first time. Generalization involves the careful arrangement of increasingly novel and varied opportunities for the student to experience success practicing / displaying the skill.

Prompting: The temporary supports that you provide as the individual is learning a skill. Your goal is to fade out all of the prompts to ensure that the individual is attending to natural cues in the environment. These prompts might be verbal, physical, gestural, modeling, or positional in type.

Practice the skill in multiple settings.

Holistic Perspective: Seeing the big picture; perceiving the whole and not just its parts; seeing the “forest from the trees,” so to speak

Using the same example as above, the student should not only practice initiating a conversation with multiple people, but also in multiple settings. Specifically, the student could practice initiating a conversation with a cafeteria worker in the cafeteria. They could practice initiating a conversation with a peer while waiting for the bus. And, they could be given the homework assignment of practicing initiating a conversation with a parent at home. Thus, the skill is being practiced in a variety of different types of settings, as well as with multiple people.

It is important to note that as each new setting is targeted, the instructor may need to initially provide close monitoring, feedback, and perhaps prompting that is quickly and systematically faded. Generalization involves much more than just sending a student into a new environment and hoping that the student will display the behavior, the first time. Each new setting should be viewed as a new instructional context in which you carefully arrange opportunities for the student to experience success practicing / displaying the new skill.

Target the skill / concept using multiple materials, examples, stimuli, and representations.

As another example, if you are teaching a client to distinguish between safe pedestrian cross walk areas versus no-cross zones, you cannot simply target one particular intersection in that community and assume that he will then correctly discriminate between safe and unsafe areas. It would be important to teach the client to recognize and respond to multiple versions of a crosswalk zone (and of course in multiple community locations).

For any student, do you use just one math problem to teach a mathematical concept or procedure? Rather, you present multiple math problems that all underscore that same concept or procedure. In doing so, you are paving the path the generalization.

Practice the skill during various tasks or activities.

Intersperse practice opportunities

In the beginning of the generalization process, the practice opportunities should be quite frequent. However, as the student begins to master the skills in the various contexts, the practice opportunities can be faded.

Practice opportunities should be naturalistic.

Arrange reinforcing consequences that are likely to occur naturally in the generalized contexts.

Extrinsic, Artificial: When the consequence is one that is artificially connected to the behavior (extrinsic in nature), this behavior may be less likely to generalize to other contexts. That artificial or extrinsic consequence might not operate in other contexts because you are not there to deliver it, or the environment simply is not conducive to that artificial reinforcer.

In generalized settings and conditions, it is more likely that the individual will experience reinforcement on an intermittent basis. This intermittent schedule of reinforcement is what often sustains behavior in the long run. Intermittent intrinsic reinforcement is what most of us naturally experience in a wide variety of contexts. Therefore, in order to set your student up for success across all school and vocational environments, it is important to:

- Arrange and deliver reinforcing consequences that are intrinsically / naturally tied to the behavior you want to see because these types of reinforcers, as well as the frequency of their occurrence, match what happens in naturalistic, generalized settings.

- Devise a plan for how you will systematically fade out reinforcing consequences that are artificial / extrinsic to the current and future contexts and targeted behavior.

Intermittent: Not continuous, often variable and unpredictable in frequency. When an employee completes his reports on time and with no errors, sometimes he is praised by his supervisor, and sometimes he is not. The employee’s efficient, accurate work is reinforced on an intermittent basis.

Use visual supports that will aid in generalization.

For example, when teaching appropriate conversation topics to use at work, you may first teach the concept by having the student use a graphic organizer to sort various conversation topics based on whether they are appropriate vs. inappropriate. The sorting task teaches the concept, but then you will need to determine a strategy that can be used to remind the student of the concept in another setting. In this example, a written list of topics to avoid at the workplace that can be kept at the student’s desk or in his pocket may serve that purpose. Thus, the skill was taught using a visual sorting task, but then a simplified written list serves as a visual reminder to transfer that skill to a real life setting.

Do a trial run.

Review strategies directly before the student is to use them.

Monitor the student to ensure that generalization is occurring.

Plan for generalization right from the start. Begin with the end in mind!