Using Interests to Build Engagement

All people are drawn to activity that allows them to engage in their interests. Incorporating the student’s unique interests into various aspects of the environment and the work tasks promotes focus and investment on quality and performance. By addressing preferences, investment and enjoyment can be enhanced and thereby improve performance.

All people are drawn to activity that allows them to engage in their interests. Incorporating the student’s unique interests into various aspects of the environment and the work tasks promotes focus and investment on quality and performance. By addressing preferences, investment and enjoyment can be enhanced and thereby improve performance.

First, when possible, find work tasks that are intrinsically motivating to the student. Intrinsic motivation means that the person is motivated from within to do a good job, not by some outside (extrinsic) motivator. For a person to be self-motivated, they must enjoy their work, have an interest in their work, and be invested in their work. If the person is interested in their job and responsibilities, they will be more motivated to complete them in a timely and accurate manner. And even more importantly, when the individual is invested in and enjoys their work, this contributes to their sense of pride, satisfaction, and overarching quality of life. This is something that every individual deserves to experience.

The priming process often provides a means of connecting the performance of a new skill with what is motivating to the individual .

The priming process involves the process of getting agreement with the student when he is resistant to change. The priming process requires intervention to get agreement that there is a different way of looking at the problem and that ‘trying a new way’ is worth the effort. The priming process involves:

- Getting agreement on the problem

- Getting agreement on the solution

- Creating the motivation for change

Does the work setting take advantage of the student’s particular strengths and preferences for activity? Is the task in any way related to his areas of interest? Even if all work tasks are not related to the student’s primary interests, finding ways to intersperse work tasks so that non-preferred tasks are followed by preferred tasks in the work schedule or ‘to do list’ is desirable.

Second, when possible, build the student’s interests into aspects of his classroom or work environment by incorporating interests into the visual supports that the student will use in the setting. Can there be time for the student to browse through his favorite reference book or for him to draw in a journal while on break or after lunch? Is there a way to for him to use his personal tablet or other technology to complete job tasks?

Will additional reinforcement be added by providing reinforcement for completion of certain tasks, for completing his work day according to specific standards, for following specific visual rules for a certain amount of time?

As you seek to promote and capitalize on a student’s motivation, keep in mind that his or her interests will change over time. Furthermore, what is motivating in one moment might not be motivating in the next moment. For example, a student might be motivated to complete a work task outside. Yet if that same student has just returned from lunch, he may not be as motivated by an opportunity to complete a work task outside. It is important to continually assess your student’s motivation in order to enhance learning and performance.

Sustained work performance and focus can be challenging to maintain in the student. The match between an individual and their job often involves capitalizing on the strengths and interests of the individual.

Strategies to promote and sustain motivation in school and on the job:

1. Identify jobs, internships, volunteer positions, or leadership roles that match the individual’s interests.

Examples:

- Someone interested in animals may be suited to work at a pet store, zoo, or veterinarian’s office. This individual may volunteer at a local animal shelter or dog park.

- Someone interested in math may be suited for a job at an accounting firm or department.

- Someone who loves the outdoors may be suited for a job in landscaping, forestry, or construction.

- Someone interested in movies may be suited to work at a video rental store, the movie theater, or a video distribution and mailing center.

- Someone who enjoys cooking may be suited to work in a restaurant or food production facility, volunteer at a food shelter or soup kitchen, or complete on-campus training components in the school cafeteria.

In these examples, the actual job matches the student/employee’s interests.

2. Make sure the actual tasks that the individual does at work are of interest.

Click Here to download and print the Preference Survey.

Examples:

Examples:

A person who enjoys categorizing or sorting:

- At a plant nursery, the student/employee could categorize the inventory, organize the plants on the shelves, and file paperwork in the backroom.

- At a restaurant, the student/employee could organize flatware, sort the recycling, and organize food supplies in the pantry or kitchen.

- In the school media center, the student could file books and periodicals.

- In a school or community-based recycling center, the employee could sort plastic, cardboard, aluminum, and paper materials into different bins.

A person who enjoys repairing or programming computers:

- At a retail setting, the student/employee could enter accounting data, type in orders, or repair computers and other devices as needed.

- At a bank, the student/employee could enter data as needed, update software and programs, or provide technical support to customers or other employees.

- After school or during the summer, a student volunteer could provide technical support to school staff.

Although the type of job may not initially appear to match the student/employee’s interests, the actual tasks that they do at the job do align with their interests.

3. Play to the individual’s strengths. People like to do things that they are good at.

Examples:

- Someone who is meticulous and detail-oriented may be well-suited for data entry or a mail room position.

- Someone who is good at categorizing may be well-suited for a job in stocking shelves, filing, or sorting recyclables.

- Someone with a strong memory may enjoy giving history tours at a museum or providing information at a reference desk at the library.

4. Intersperse non-preferred and preferred tasks in the work schedule or ‘to do list.’

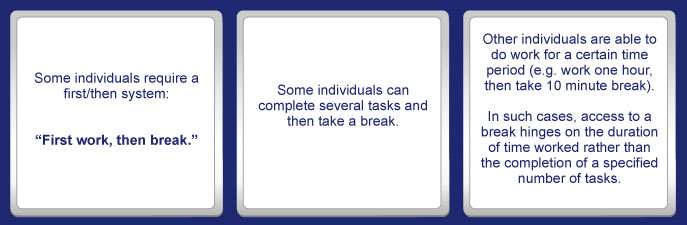

In order to maintain stamina and attention, most of us need the interspersal of more and less preferred activities within our work schedules. Some individuals might want to complete all of the less preferred tasks and then move on to the preferred tasks. Other individuals might respond better to true interspersal, where they complete several less preferred tasks, then a few preferred tasks, then a less preferred task, etc.

In order to maintain stamina and attention, most of us need the interspersal of more and less preferred activities within our work schedules. Some individuals might want to complete all of the less preferred tasks and then move on to the preferred tasks. Other individuals might respond better to true interspersal, where they complete several less preferred tasks, then a few preferred tasks, then a less preferred task, etc.

When arranging the task sequence, it is important to carefully assess the organizational, self-direction, and self-regulation skills of your student (and the conditions of the work environment). Depending on the needs of the student and the nature of the work tasks, modifications to the interspersal sequence might need to occur on a daily basis.

Examples:

- A student who works in a school media center prefers organizing and filing books and data entry tasks, but she does not prefer other required tasks such as wiping down shelves, organizing magazines, or making copies. For this student, you have determined that she would best maintain stamina and accuracy if she completes several preferred tasks followed by a less preferred task, and then several preferred tasks again, followed by a less preferred task, and so on.

- A student / employee works at a local plant nursery. You have determined that this individual is most productive when he can complete all of his less preferred tasks in the morning, then take his lunch break, and then move on to more preferred tasks in the afternoon.

5. When teaching new skills in the school or work setting, intersperse learning tasks so that familiar, less challenging tasks are mixed with new, more challenging tasks.

The learner needs to experience success in order to maintain stamina and to prevent frustration. Thus, in order to reduce frustration, it is important to combine new teaching tasks with tasks where the student can easily experience success and a sense of mastery.

Examples:

- You are teaching your student how to accurately visually distinguish between new versus closed purchase orders in the school bookstore. This is the unfamiliar, more challenging task. As you teach this task over a series of teaching sessions, you should also intersperse familiar tasks into the instructional session– tasks that the student can already perform with relative ease and limited frustration. These tasks might include sorting periodicals into bins and affixing scanning codes to new books.

- You have been working with your client on teaching a coping strategy (i.e. a sequence of muscle relaxation exercises) that he can practice and use on the job. In previous teaching sessions, this client has learned how to perform fist tension and release, and shoulder tension and release exercises. He is now familiar with these exercises and can complete them independently using a visual aid. The new teaching task is a facial tension and release exercise. As you teach this new skill across instructional sessions, you should also intersperse the previously learned tasks (i.e. fist and shoulder release exercises).

6. Incorporate the individual’s unique interests into their visual supports.

Visual supports would include environmental design features, visual schedules, to-do lists, graphic organizers, social narratives, video models, visual scripts, and visual cues.

Visual supports would include environmental design features, visual schedules, to-do lists, graphic organizers, social narratives, video models, visual scripts, and visual cues.

Here are examples of ways to incorporate the individual’s interests into these visual supports:

- If your student/employee is really interested in trains, incorporate trains into their schedule or to do list. For example, have their “check schedule” card be a picture of a train.

- If your student /employee is interested in meteorology, incorporate images of different weather systems into his matching to do list.

- If your student/employee is interested in technology, support their use of an electronic device to access their schedule and to do list.

If your student/employee has a strong interest in particular movie characters or genres, incorporate those elements into their social narratives (i.e. coping cards).

7. Consider the use of extrinsic motivators when needed.

Many times, simply incorporating someone’s interests is enough to keep them motivated and happy at the job. However, sometimes additional motivation is necessary. This is where extrinsic motivation comes into play. Extrinsic motivation means that you are motivating someone using outside motivators- something more than their inner drive to motivate them. The majority of us are motivated by extrinsic motivators, the most common being money. Without a pay check, many of us would not work! Thus, extrinsic motivators are very important.

When thinking about motivators, consider things that may be reinforcing to the individual. It is also important to arrange reinforcing consequences that are inherently, naturally related to the task. The type of reinforcers that work for your student/employee will depend on the individual’s level of functioning, and of course, their interests.

Examples of Extrinsic Motivators:

Breaks are generally the most effective way to motivate someone. If you complete your work, you get a break.

- When incorporating breaks to motivate your student/employee, first think about their level of functioning. What types of contingencies does this individual understand?

- Next, consider what the student/employee is to do during his break. A break is only motivating if the individual looks forward to it and likes what he does during break. What may be relaxing and fun to you may not actually be appealing at all for someone , so it is important to determine what the individual likes to do. This is another great way to capitalize on interests:

- Does he have a strong interest in trains? If so, he might read train books, look at train videos on youtube.com, or complete a train-related word search.

- Does he relax by listening to music? If so, he might use a computer, phone, or iPod to listen to preferred music.

- Does he prefer to be alone during a break? Or, does he prefer to engage in social conversations during break?

- Finally, make sure that this information is clearly presented to your student/employee. Include breaks on the schedules or to do lists so that he can visually see that he is making progress and nearing break.

Sometimes, working towards a special reward or event can be motivating to an individual .

Like breaks, these rewards or special events should be individualized to the person so that he is actually motivated by them.

- For example, add in “Outing to the library” at the end of your student’s schedule so that he can see that something fun and enjoyable comes at the end of his work day.

- Or, provide the student/employee with a choice board showing written options or images of preferred activities that he can engage in after completing tasks.

- Some individuals may enjoy a tangible reward, such as choosing a gadget or item from a “reward box” or even edible reinforcers, such as a candy bar.

While some individuals are not motivated by conventional social praise, such as their teacher’s or supervisor’s approval many are!

Praise is a great way to motivate someone and should be used whether or not the student/employee seems to respond to it if they did a good job. However, it is important to note that some individuals prefer to receive praise in private rather than in front of their peers or coworkers. In such cases, private praise could be delivered in a 1:1 meeting, on a written note, or via email.

Be specific about praise. Let the student/employee know exactly what you liked about their performance. Rather than saying, “Nice job,” say, “You did a really nice job completing this task so accurately,” or “You did a nice job handling that customer calmly.”

For some individuals , deadlines can be motivating.

Providing a specific due date as to when to complete a task can provide a sense of structure and help organize some people. Without having a due date, some might procrastinate and are not able to self-motivate to complete a task. Breaking a project down into smaller steps, each with their own deadline, can also be helpful. Using daily, weekly, or monthly calendars, depending on the length of time until the due date, should be used in conjunction with deadlines.

Deadlines, however, are not motivating for all individuals. Some individuals may become anxious regarding an impending deadline. Thus, in some cases, it might not be helpful or constructive to emphasize an impending deadline.

Some individuals may be motivated by money or a token system.

However, some individuals may not be motivated by money because it is not an immediate enough reinforcer, and it is too abstract a concept. For those not motivated by money, a token system that leads to specific reinforcing activity (or choice from a “menu” of activities) may be more effective. In a token system, the individual is given a token immediately after the completion of a task well-done. He can later use accumulated tokens for a larger reward. While token systems can sometimes be effective, this multi-step, somewhat abstract approach may not be the most motivating tactic for some individuals on the spectrum.