First, it is important to state that communication systems and scripts should provide the student with a means to initiate communication based on their motivation– to ask for a drink, to request assistance, to greet a peer, to end a conversation, to make a comment, etc. Communication systems and scripts are the vehicles by which some individuals expressively communicate. This expressive communication might come in the form of a gesture, a facial expression, a picture exchange, a point to a symbol, a voice output transmission, sign language, and simple words and phrases up through fluent dialoguing.

First, it is important to state that communication systems and scripts should provide the student with a means to initiate communication based on their motivation– to ask for a drink, to request assistance, to greet a peer, to end a conversation, to make a comment, etc. Communication systems and scripts are the vehicles by which some individuals expressively communicate. This expressive communication might come in the form of a gesture, a facial expression, a picture exchange, a point to a symbol, a voice output transmission, sign language, and simple words and phrases up through fluent dialoguing.

What Does the Individual Initiate?

Individuals with significant behavioral difficulties frequently have limited ways of communicating their wants and needs in an appropriate way. They may not initiate communication with words or sign language, pictures or objects, but with biting, scratching, property destruction or other behaviors that express their internal states and needs. In far too many cases, individuals whom we describe as ‘verbal’ only respond to communication initiated by others, or they require specific prompts to ‘communicate’ or initiate a message.

The communication process is reciprocal, not a one-way street. If we only teach responses, communication is ineffective and the outcome well may be inappropriate behaviors. The two-way street of communication requires reciprocal interaction in the form of both initiations and responses. A primary goal of communication training is to increase the number of communication closures. A communication closure involves the initiation of a message by one individual and the response by another to that message. Our goal is to support frequent communication closures. Assuring that the individual initiates communication within the process of exchange is pivotal. If I ask a student, “what do you want?” I must be aware that I am building responses, not initiations. If I see that a student is distressed and I say, “Tell me how you are feeling,” I must be aware that I am building responses, not initiations.

Many families express the very appropriate concern that they want their child to talk. This is certainly important. However, the priority needs to be a meaningful way to express or initiate communication of various messages. This priority necessitates providing a functional communication assessment as a means of identifying the messages that are crucial to the student. The functional communication assessment defines what the student needs to communicate, not what the teacher needs the student to communicate.Providing a functional communication assessment can determine targets of communication training that will support successful post-school outcomes. In the functional communication process, the presence of inappropriate behaviors is often a signal that the individual needs to be taught a better way to communicate at least one type of message.

Many individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome have noted that knowing how to talk follows knowing why to talk. Repeatedly over the past 20 years, Jim Sinclair and many others have provided stories describing how they did not figure out until they were much older that talking could help them obtain what they wanted or needed. Simply stated, assure that a student can initiate communication with various messages while ‘teaching the student to talk.’ Initiations can involve gestures, signs, pictures, facial expressions, or even objects. Adding an expectation of verbalization to the use of pictures, gestures, or objects is a long-term goal. Getting the person to initiate should be a first step.

Initiation as an Issue for Nearly All Individuals

There are many verbal individuals who have difficulty retrieving the right words called for in specific social situations due to anxiety, confusion, and over-stimulation. Individuals who can communicate basic physical needs or desires for activity may ‘freeze up’ or not know what to say in specific social exchanges. Individuals with an ability to communicate basic needs may not have skills to ask for help when materials are missing or broken, to request an end to an activity, to retell a stressful event, to communicate fatigue or to communicate that something is bothering them. Sustaining conversation may be extremely difficult. Within Unit 2 – Job Seeking & Unit 3 – Job Keeping, there are multiple objectives that can assist the instructor in completing a functional communication assessment related to future post-secondary environments. The results of your assessment might reveal that your student needs a simple journal to express his feelings, visual scripts to aid in simulated practice sessions, topic cards to support appropriate topic selection, or discrete visual scripts to carry in his wallet as he approaches a real social situation.

Selecting a Communication System

The use of sign language can serve to enhance the individual’s communication. However, how well sign will be understood in future community environments is a consideration for those providing instruction. Will people in future environments be more responsive to visual cards and scripts than they would be to sign language? For some individuals, the Picture Exchange Communication System (P.E.C.S.) has proven to be a low-tech, yet powerful tool that emphasizes an intentional communicative exchange that is initiated by the individual .

In some cases, it will be easier for peers in the future to respond to the individual equipped with voice output technology. If an individual needs communication supports, the system must support future interaction. Moreover, communication systems that provide a voice for the individual have proven effective for many. Voice Output Communication Aids (VOCA) are considered an evidence-based best practice for individuals who need that voice.

The Transition Toolbox contains an array of modifiable scripts that show a concrete set of written (and potentially picture) cues that provide the student with directions and words that he will use in a specific situation. The script provides visual cues for the dialogue, the interaction, and the expected behaviors in performance of a target skill. The script should be individualized to assure that it fits the needs of the student. Does he need every word of the dialogue written on the script card to support his successful performance? Does the student need additional picture or word cues to define his body position, facial expression, gestures, etc. during the use of the script?

“Act it Out” Cards: Scripts & Scenario Cards to Support Instruction

Who might benefit from the “Act it Out” cards?

Individuals in middle-school, high school, and adult life who display mild to moderate deficits in the areas of socialization, perspective-taking, communication, coping, and self-advocacy may benefit from the use of these cards in systematic practice.

Who helps teach the skills?

- Teachers

- Job coaches

- Family members

- Therapists

- Any other person offering support

Where to use them?

These cards are designed for use in small groups or 1:1 contexts. They can be used in almost any setting:

- Educational

- Vocational

- In-home

- Therapeutic clinics

- Community

- Wherever an opportunity to practice arises

Why use them?

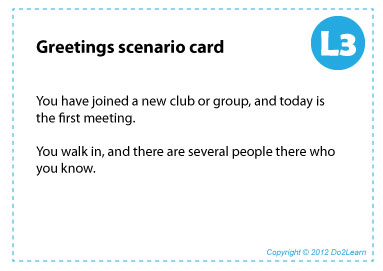

Merely talking about how to perform a certain skill is not sufficient. Students with learning differences often struggle to identify and practice all of the complex verbal and nonverbal responses of a seemingly simple exchange. Students with social skills deficits require multiple opportunities to practice these responses in a safe environment. These “Act it Out” cards allow instructors to break down target responses into recognizable parts to focus on what to say, how to say it, and what to do in a variety of situations.

When to use them?

Once the priming process is completed and agreement is reached on the targeted skill, the teaching process of modeling, practice & role-playing begins. Within that teaching process, the instructor may determine that specific visual supports like scripts or scenario cards would support the student’s performance in the teaching process.

Priming: Priming involves the process of getting agreement with the student when he is resistant to change. The priming process requires intervention to get agreement that there is a different way of looking at the problem and that ‘trying a new way’ is worth the effort. In this case, the priming process often involves the use of a graphic organizer or social narrative (visual supports) to promote a shift in perspective and to promote “buy-in.”

Preparation Phase

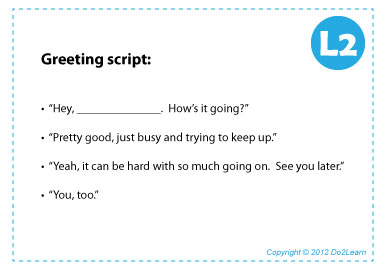

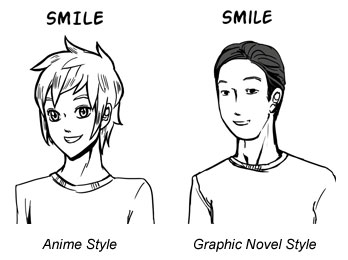

As you prepare the cards, the key is to individualize the tool to best meet the needs of your student. Your student might need a modified script, and your student might respond better to our anime style picture cues versus our graphic novel style picture cues.

As you prepare the cards, the key is to individualize the tool to best meet the needs of your student. Your student might need a modified script, and your student might respond better to our anime style picture cues versus our graphic novel style picture cues.

- Determine which card level is the appropriate starting point for your student(s).

- If needed, modify the existing card set through your View2Learn program. This full card set is also housed in View2Learn for you to modify scripts and individualize the insertion of picture cues as needed. Practice will likely lead to changing the script to support the comfort and skill of the student. It is also very likely that you will need to create brand new scripts to address additional topic areas.

- If needed, modify the type, size and placement of the “Act it Out Picture Cues” through View2Learn. All of the “Act it Out Picture Cues” are housed in View2Learn, so you can select and arrange the right cues for your student – anime style, graphic novel style, or stick figure.

- Print card set and picture cues in color.

- Laminate cards and picture cues.

- Cut out each card.

- Determine the scope and sequence of use. You might select scenarios based on current areas of need for particular students.

Instructional Phase

It is important that the focus of the role-play is on developing the scenario-specific skills and not on teaching the visual cues. Therefore, it is highly recommended that “Act it Out Picture Cues” are taught prior to conducting role-plays.

- Select the type of picture cues that your student(s) might best respond to – anime style, graphic novel style, or stick figure style. Then, print and begin using the included “Act it Out Picture Cues” in practice sessions.

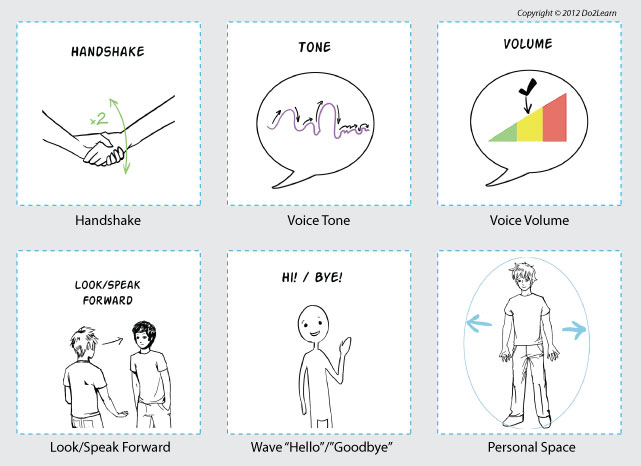

- Use these visuals as references throughout the learning process to promote development of skills well before conducting role-plays. Use the visuals to teach skills such as voice volume, standing straight, and shaking hands throughout the learning process. This will help learners become more familiar with the visuals’ meanings prior to being expected to practice the skills during the “Act it Out” role-play activity.

- Have the visuals available during role-plays for easy referencing. If learners need prompting, try gesturing toward the necessary visuals instead of explicitly telling them what to do. Gestural prompts are much easier to fade than verbal prompts.

Picture Cues:

When introducing a scenario:

- Assure that all concepts of the scenario have been understood and practiced by the student.

- Label the skills that will be practiced.

- Assign roles or request volunteers to assume parts in each scenario. All scenarios contain 2 or more actors per scene.

- Explain the context or circumstances of the scenario as needed to help the student act with confidence. Set the scene.

- Clearly indicate the “marks” where each actor should be. Will you need tape on the floor as an environmental design component? What items will you use as props? Do you need other visual supports (structure) to clarify where to be and what to do?

- If necessary, provide the visual cues within view of the actors. The “Act it Out Picture Cues” can be placed on the floor, on a desk, or posted to a wall.

- A “scene walkthrough” may help clarify where each actor should be, when to speak, and what to do during the scene. Think of a walkthrough as a hands-on assisted rehearsal.

Set the scene: If you are targeting the “Asking Someone to be a Reference” scenario, the student has previously demonstrated understanding of the concept of ‘reference’ during the instructional process. There has been previous review of a ‘good reference,’ ‘reference letter,’ and the characteristics and content of a reference. Reminders or initial practice of the expected skills with a script will often be important before jumping into scenarios. As the student reads the scenario, describe the context and help the student ‘set the stage’ for the role-play. Reduce the student’s anxiety or confusion. Make the role-play as engaging and fun as possible.

Provide positive feedback and offer praise for effort and display of skills.

- If corrections are needed, identify what to do. Can another student model the expected behavior? Can you encourage the student to identify how to self-correct?

- Have students identify the “wrong way” and then have them practice the correct way. This will help clarify the appropriate and inappropriate responses.

- If possible, record the role-plays for self-review by the students. Replaying videos for students allows them to see themselves, offering an opportunity for expanding perspective-taking. Videos can be paused to focus on details, such as facial expressions, which can help solidify the many abstract skills required in each scenario. It is important to make sure students are comfortable being recorded and watching recordings of themselves before initiating this technique.

Elements of Direct Instruction

Within the process of reciprocal exchange, a major goal is increasing the frequency of communication closures, that is, integrated initiations and responses in dialogue. Boosting frequency and variety can increase confidence and generalization. Practice creates fluency. Working on communication efficiency requires careful attention to the issues described in this instrument’s section on generalization.

In summary, communication systems come in many forms, and this wide array is reflective of the varied and unique needs of individuals on the autism spectrum. Yet all communication systems should be devised with these basic principles in mind:

- The communication system should provide the individual a way to communicate his wants and needs, whether those messages come in the most basic (“juice”) or more complex forms (“Let’s go to the movies this weekend”).

- The communication system is the vehicle by which the individual can initiate communication.

- The individual’s use of the communication system is activated (elicited) by their own motivation to communicate something. The communication system provides the individual a means to express himself. Its purpose is not for the instructor to express an idea or directive to the individual.

- All individuals will need practice in using some augmentative device to support their initiation of a specific message. Careful attention to the elements of direct instruction is crucial.