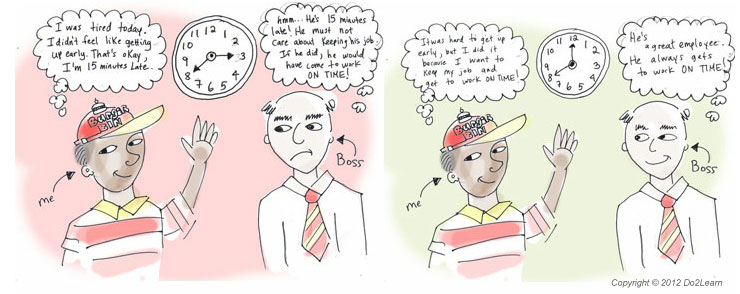

Thought stories are very similar to coping comics in that they use drawings or comics to clarify attribution (details that explain why something happened) or perspective (what someone is thinking). The main difference between the two strategies is that coping comics use open dialog (back and forth conversations) to teach what to do or say in certain situations. Thought stories use thought bubbles to show what people are thinking.

Attribution: The process of recognizing key details in the environment and in the behavior of others that identify WHY something is happening. Attribution requires connecting the significant details of a situation to understand the behavior of others. Attribution is a foundation skill for the development of perspective-taking.

Perspective-taking: The process of recognizing WHAT a person is thinking in a situation. Once a person has the skill of identifying details of human behavior and circumstance (attribution), can we define ‘the thoughts’ of the other person? Perspective-taking requires reading more complex details like facial expression, body language, and tone of voice to use in social problem-solving.

The thought story may also highlight important environmental details that affect others’ thinking. For instance, a thought story may help the individual understand why his friend did not speak to him on the way to class. The thought story may show a clock on the wall showing the time for the beginning of class, may show a bell ringing, may show the other person running and juggling books. These details are related to the thought bubble over the friend’s head that says, “I can’t be late today.” By portraying both the concrete details and the thought bubble, the thought story helps explain the friend’s behavior of not saying “hello” in the hall. Thus, thought stories teach social nuances, attribution, and perspective taking that individuals may miss.

How to design and use thought stories:

- Focus on one concept at time. Do not overwhelm your student by teaching too many perspectives in a single thought story.

- Create the thought story with your student. You can draw the thought story for your student, or you can have him draw his own. A collaborative process will promote student involvement and buy-in, but also allow you to guide the student in appropriate responses. You will under most circumstances need to actively portray the concrete details that are relevant to the thought bubble.

- Neither you nor the student needs to be a good artist in order to develop an effective thought story. Stick figures are perfectly acceptable. As another option, you or your student could also cut and paste people (or preferred characters) from magazines, printed Google images, and more. If you pursue this option, you would need to write in thought bubbles and text to accompany the characters.

- The thought story should be reviewed frequently to be the most effective. Ask the student questions about the thought story to ensure their understanding. Or, write down a few questions if your student responds better to written information Answers could be provided by circling the correct response if your student has difficulty with open-ended questions. Your goal is to help the student connect the details to the person’s thinking.

- Store the thought story in an accessible and portable place, such as a notebook, binder, or taped to the top of their agenda.