In what contexts does the student need to display this skill, now and in the future?

Identifying and responding to anxiety is necessary for healthy functioning in all areas of life: personal, social, professional, etc. An individual with skills to recognize personal signs of stress and who is able to associate stress with specific triggers is much more likely to develop healthy coping strategies for future success.

What are the steps that comprise this skill?

individuals often have difficulty dealing with and using abstract concepts that occur in varying contexts. Many experience extreme difficulty comprehending and applying emotional concepts, like anxiety. The instructor must adjust instruction to address the detail-oriented thinking of the individual.. Thus, target selection will most often start with concrete details that the student can label and act on. Are there specific behaviors that the student can define in himself? Are there clear events, tasks, places, or people that trigger anxiety for the student?

Comprehension of the abstract concept of ‘anxiety’ will often follow as a result of connecting multiple examples of the anxious behaviors and thoughts, with their circumstances. The goal of labeling ‘anxiety’ is important. However, for some, it is essential to label it in terms that support identification of behaviors, identification of circumstances and what to do concretely to cope. Labeling this as “anxiety” is not necessarily the immediate goal.

Initially, the instructor helps the student define both specific behaviors and triggers in a way the student can accept and comprehend. For each student, these behaviors or feelings may be described as ‘bad’ or ‘uncomfortable’ or ones he ‘wants to go away.’

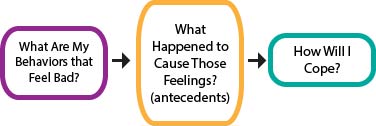

However, for the individual learning to eventually recognize this sequence, it may help to approach the instruction of this skill with a sequence that helps the student focus on the concrete behavior first. Consider the following sequence of questions as an instructional sequence:

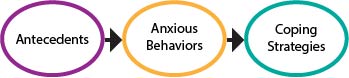

When we look at the temporal sequence in the experience of coping with anxiety, antecedent or trigger events (and sometimes thoughts) are followed by anxious behaviors which are then hopefully followed by coping strategies that alleviate the stress.

To comprehend the relationship between antecedents and behaviors, the student may need to work backwards from his own behaviors to the antecedents or triggers. Using a sequential process for self-regulating anxiety requires comprehending this connection.

*Please keep in mind how ‘thoughts’ can play two different roles in this sequence. In some cases, an individual may have a recurring thought (“I was thinking about what happened to me on Oct. 12, 1997, when my mother was in a car crash…”) that acts as an antecedent to specific physical behaviors (crying, wringing hands, biting self, etc.).

In other cases, concrete events (supervisor says, “Get a move on, I need this finished in 5 minutes.”) act as antecedents that lead to physical behaviors and possibly to anxious thoughts (“I can’t do it. I am going to get fired.”). Thoughts can be antecedents or behaviors, depending on the individual. The instructor must work with the student to determine whether the thought triggers the anxiety or whether other events trigger the anxious thought.

What sub-skill should you target first for the student to initiate? Given what the student can do presently, how will you present the task so that the student can perform steps within his capacity while learning a new step?

The entry point for teaching about identifying and coping with anxiety often depends on what the student does when upset. If the instructor has chosen this topic for intervention, the instructor should have data on the disruptive behaviors including the antecedents that lead to the student’s anxious behaviors. Two different data sheets are posted below for your consideration and use:

Whenever possible, begin by defining the specific behaviors in which the student engages when upset. The student may deny certain labels and may even deny engaging in certain behaviors. Talking about this behavior with the student may actually lead to the behavior or other significant signs of stress. How you approach this will be addressed more completely in Motivation and Priming. As an instructor, you are creating a problem-solving model for self-control of anxiety. This involves three steps:

This problem-solving model is likely to be the same sequence regardless of the student’s ability. How it is expressed or displayed is what will require adaptation to fit the student’s thinking. Over time, with multiple examples and with some success in self-control, it may come to be labeled “anxiety.”

As Temple Grandin notes so eloquently in Thinking in Pictures, people can learn concepts, but they learn them often by connecting details or multiple examples. Over time, as you work on the three-step model, you may begin to label those behaviors as ‘anxiety,’ ‘worry,’ ‘upset,’ ‘bad feelings’ or some other descriptor of the student’s choosing. He or she will understand and use the concept as he experiences success in the process.